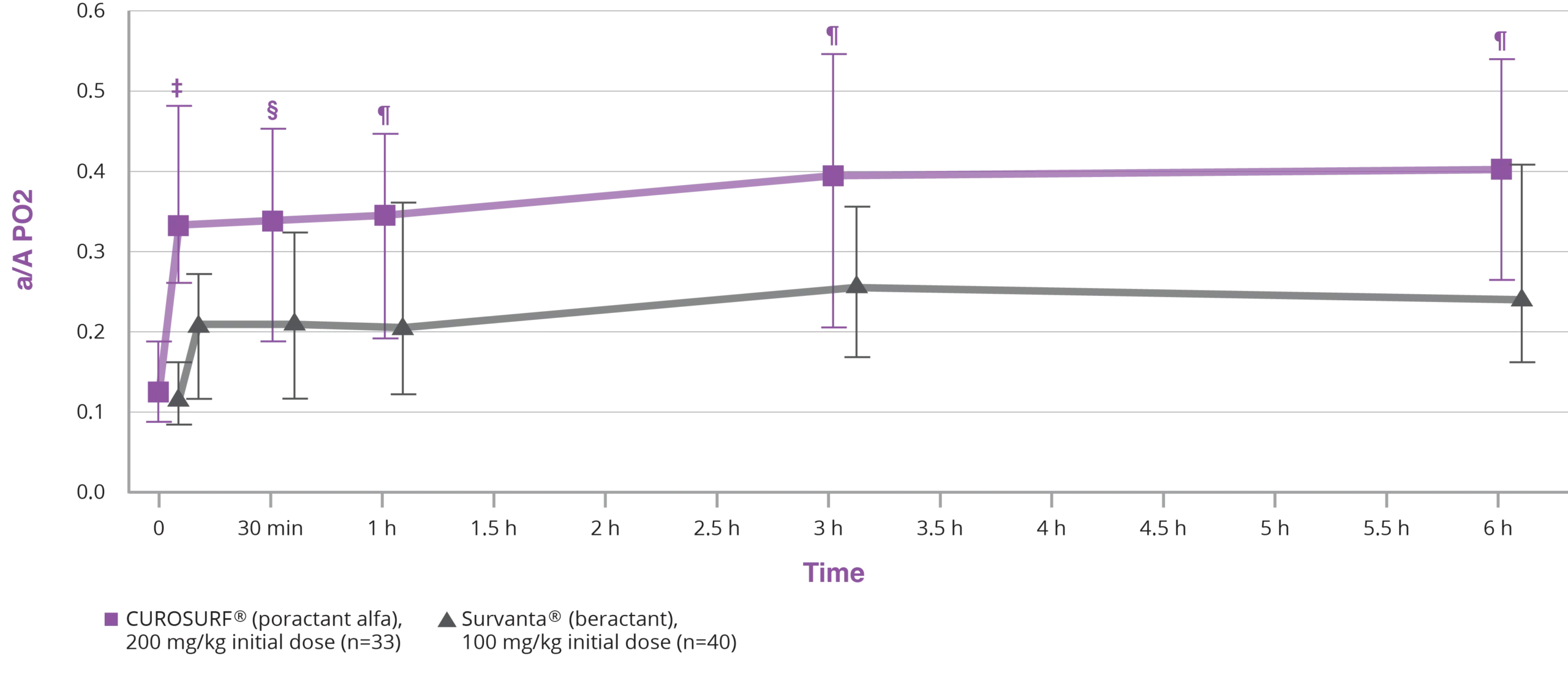

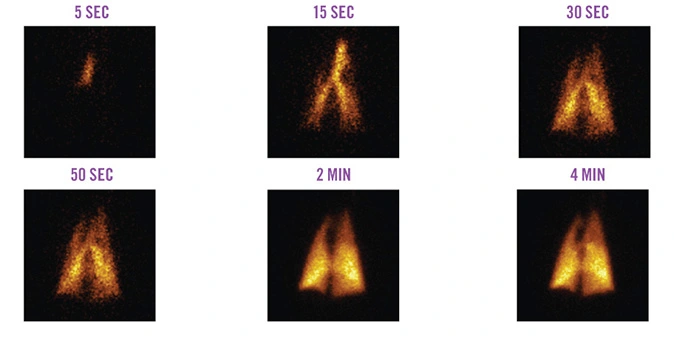

References: 1. Speer CP, Gefeller O, Groneck P, et al. Arch Dis Child. 1995;72:F8-F13. 2. Collaborative European Multicenter Study Group. Pediatrics. 1988;82:683-691. 3. Ramanathan R, Rasmussen MR, Gerstmann DR, Finer N, Sekar K; And The North American Study Group. Am J Perinatol. 2004;21:109-119. 4. Verder H, Albertsen P, Ebbesen F, et al. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1-6. 5. Dizdar EA, Sari FN, Aydemir C, et al. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29:95-100. 6. Karadag N, Dilli D, Zenciroglu A, Aydin B, Beken S, Okumus N. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:1015-1022. 7. Malloy CA, Nicoski P, Muraskas JK. Acta Pediatr. 2005;94:779-784. 8. Fujii AM, Patel SM, Allen R, et al. J Perinatol. 2010;30:665-670. 9. Gerdes JS, Seiberlich W, Sivieri EM, et al. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2006;11:92-100. 10. CUROSURF® (poractant alfa) Intratracheal Suspension Prescribing Information, Chiesi USA, Inc. May 2021. 11.Survanta® (beractant) Intratracheal Suspension Prescribing Information, AbbVie, Inc. October 2020. 12. Infasurf® (calfactant) Intratracheal Suspension Prescribing Information, ONY, Inc, March 2018. 13. Moya FR, Gadzinowski J, Bancalari E, et al. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1018-1029. 14. Sinha SK, Lacaze-Masmonteil T, Valls I, et al. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1030-1038. 15. Ingimarsson J, Björklund L, Jonson B, et al. Biol Neonate. 2000;77(suppl 1):24. 16. Schürch S, Schürch D, Curstedt T, Robertson B. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:974-986. 17. Wiseman IR, Bryson HM. Drugs. 1994;48:386-403.